This article is about Pisa, city of the Tuscany region a place to visit even if you live in Rome.

LEOPARDI VERSUS LEOPARDI

Pisa, the Lungarno and the appetite of the “The fabulous young man “.

There are places that you feel inside, and without realizing it, they change you. So happened to Leopardi. In Pisa he lived a completely new period, a different era, asa a writer and as a man. “I have found here in Pisa a delicious street, which I call Via delle Rimembranze: I go there for walking when I want to dream with open eyes ” wrote the Poet .

There is a short distance between Pisa and Florence, the city where he lived previously, but it is great the distance between the Florentine Leopardi and the one who lived and worked in Pisa.

There is a short distance between Pisa and Florence, the city where he lived previously, but it is great the distance between the Florentine Leopardi and the one who lived and worked in Pisa.

So the question is the following: was the city of Pisa to transform the Poet , or simply allowed him to express what he always had inside, an essential component of his way of being and feeling , his alternative or even main nature?

“To the future generations the hard answer”, would have said a distinguished colleague of Leopardi.

The problem is that we, hic et nunc , much later, are still largely uncertain about a possible answer.

As Montale would say, “everything we know is what we have not , what is not” .

Certainly Leopardi was not the deformed and lackluster figure described by many school books in Bignami style.

Leopardi was not the “pessimist” that underlines the fleeting beauty of the Saturday later frustrated by the disillusioning Sunday . It’s not what the teenagers of our time, with a hasty but effective definition, would call a “hunchback loser “

Leopardi was not only the man bent over sweaty papers or imprisoned in the library of his father, already completely wrote at an early age . Leopardi is this , but it is also, and perhaps above all, a man greedy of life, that same life which he watched with a philosophical and rigorous eye, but never stopping to look at her with deep interest and natural curiosity.

He is also the man who while translating Greek and Jewish books writes childish dialogues for easy and light “comics” and humorous jokes. He is the gentleman of noble origins who listens carefully and passionately to the noises of his village, sounds, songs, music, catching the simplicity of their minds and souls. A gift he did not possess, but always searched for and felt fascinated by. The same vital and enigmatic charm he felt in the women that he always looked for their complex and attractive essence.

The Poet from Recanati was a lover of ancient times but he was also focused on his own time. He constantly looked for a change, not only for himself but also for his nation, a country oppressed by injustice, misery and corruption.

This complicated person and artist arrived in the right time, in the right season, in a city that looked much like him: it was rooted in the territory but it was also a meeting point of travellers, writers, philosophers, full of “salotti” rich in culture but also open to new, revolutionary ideas. Pisa, a city well known for the studies but far from being a museum, being surrounded by a pulsating beauty, the same that runs within the river and in the boulevards, the Lungarni.

In Pisa Leopardi found a conciliation between his hunger for life and the necessity to give an order to his patrimony of memories and emotions. He found stimuli but also the right place for further reasoning, new projects, new hypothesis of bridges between himself and life. From this starting point, it’s easier for us to think that the dreaming walker of Via delle Rimembranze is the same author that portrayed life as a tragedy and an evil trick. It’s easier to imagine the smile of the poet along the roads full of voices. Pisa for Leopardi was the blooming of Spring in the middle of the Winter. He arrived in Pisa in November 1827 to escape from the freezing Florence Winter, and he stayed in Pisa up to June 1828.

In one of the letter he sent to his sister Paolina he wrote: “I was enchanted by Pisa for his climate: if it will last like this it will be a bliss. I like Pisa much more than Florence. This Lungarno is a beautiful show, wide, magnificent, happy: I never saw anything similar in Florence, nor in Rome, and I really don’t know in the whole Europe you could find such a magnificent landscape. At certain hours of the day this city is full of coaches and walkers; you can hear ten or twenty languages spoken and a bright sun shines on the cafés, on the shops full of precious objects and on the wonderful houses. For the rest, Pisa is a mixture of great and small city, a romantic mixture I have never seen before. Besides, it has a beautiful tongue. And, morevover, here, thanks God, I feel well, with much appetite” (November 12, 1827).

It would not be a paradox to suggest to today’s city administrators to affix a note to the enrollment on the Lungarno dedicated Leopardi in order to remind citizens and visitors that in Pisa he found a new inspirational vein but also the appetite. Cause in this seemingly banal and prosaic note there is a great deal of poetry and the synthesis between greatness and humanity, ethereal nature and carnality.

In this era that tends to make us “virtual” beings by reducing us to smartphones’ icons , we also smile imagining the genuine impulses of a man who had made of the poetic – philosophical speech and thought its essence .

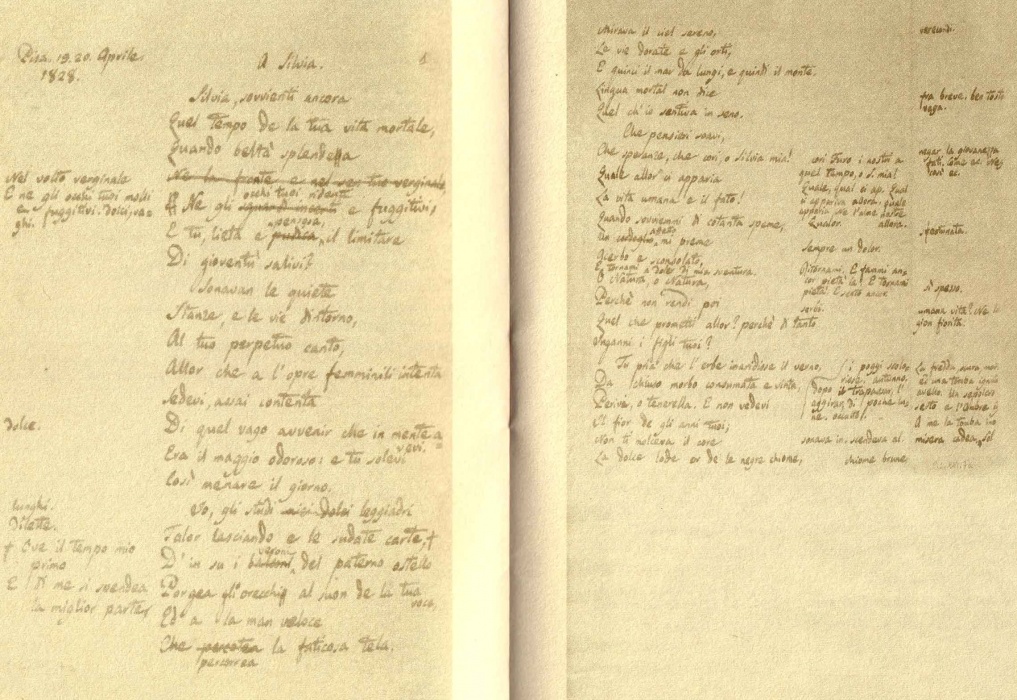

Pisa confirms to Leopardi what he already knows: his hunger for life. Pisa enables him to observe the beauty without being suffocated by the frost of reflection. The mixture of the urban and country, the worldly Pisa and the intimate city, fascinates and involves him. In this climate Leopardi will write two of his most important compositions, apparently so distant ine from the other, but basically sharing the same feeling and theme, the one of love: “A Silvia” and “Risorgimento”.

Pisa, therefore, gave him a rare and valuable opportunity for dialogue with the true himself. Perhaps Leopardi would share the words written decades later by Albert Camus: “Loneliness and thirst for love. Pisa, finally, alive and austere, with its green and yellow palaces, its domes and, along the Arno, his grace. A sensitive city. And so close to me at night when walking through the deserted streets, my desire to tears finally unleashed. The scars of my soul begin to heal. “

With the words of another writer, Gianni Rodari, maybe we can get to a conclusion that, despite its simplicity forced us one step closer to this childish and smiling hypothesis: “Mistakes are necessary, useful as bread and often beautiful: for example, the Tower of Pisa”. In Pisa Leopardi discovers that in the error of life, so crooked and asymmetrical, there is the constancy of the beauty and the beauty of a tenacity that has in itself something simple and mysterious, strong and stubborn.

Or maybe it’s our turn to discover or rediscover in our own towns, in our crowded loneliness, that there are errors, people out of any cliché, that have inside all the complexity and richness of humanity, people you cannot define with a simple formula, marked only by the changing and neverending research of a land where beauty and poetry can live and express themselves in freedom and prosperity.

by Ivano Mugnaini

A Silvia – Giacomo Leopardi – Voice: Vittorio Gassman

IVANO MUGNAINI si è laureato all’Università di Pisa. È autore di narrativa, poesia e saggistica.

Scrive per alcune riviste, tra cui “Nuova Prosa”, “Gradiva”, “Il Grandevetro”, “Samgha”, “L’ Immaginazione”. Cura il blog letterario DEDALUS: corsi, testi e contesti di volo letterario, www.ivanomugnainidedalus.wordpress.com.

Ha curato la rubrica “Panorami congeniali” sul sito della Bompiani RCS. Suoi testi sono stati letti e commentati più volte in trasmissioni radiofoniche di Rai – Radiouno. Collabora, come autore e consulente, con alcune case editrici. Cura e dirige i “Quaderni Dedalus”, annuari di narrativa contemporanea.

Ha pubblicato le raccolta di racconti LA CASA GIALLA e L’ALGEBRA DELLA VITA , i romanzi IL MIELE DEI SERVI e LIMBO MINORE.

L’algebra della vita (Greco & Greco, 2011), Inadeguato all’eterno (Felici editore, 2008), Il tempo salvato (Blu di Prussia, 2010)

Tra i critici ed autori che si sono occupati della sua attività letteraria ricordiamo: Vincenzo Consolo, Gina Lagorio, Ferdinando Camon, Raffaele Nigro, Giorgio Saviane, Paolo Maurensig ed altri.