In the beginning was Pasolini, Pier Paolo Pasolini, then he became pasoliniano. Just like Fellini is, inevitably, felliniano.

The adjective identifies the author or denies his genuine nature? Has Pasolini thought gone beyond the immanent surface of his time, and, above all, is it still up to date? In these times in which we tweet and tag it is easy to reduce the complexity of a person to an adjective. It is worth however asking ourselves whether and how Pasolini became pasoliniano.

In the beginning was Pasolini, Pier Paolo Pasolini, then he became pasoliniano. Just like Fellini is, inevitably, felliniano.

The adjective identifies the author or denies his genuine nature? Has Pasolini thought gone beyond the immanent surface of his time, and, above all, is it still up to date? In these times in which we tweet and tag it is easy to reduce the complexity of a person to an adjective. It is worth however asking ourselves whether and how Pasolini became pasoliniano.

A possible answer can be provided by the comparison with Fellini, by analogy and contrast. Both have represented their time, the years in which Italy has tried to shake off centuries of misery and subjection to cultural censorship, constraints, frustrations disguised by healthy and canonical principles. Pasolini and Fellini used in a very different way the weapons of different thinking, dreaming, and the disruptive power of sex as a liberating energy, a privileged way to knowledge, never meant and felt as mere voyeurism or as a surrogate of pornography. A change of age would surely bring , however, strong consequences, not only on a psychological level. Fellini protects the roots of his own land, both geographical and psychological, with the aura of a dreamy vision, a film in a film that can transform a landscape into a place of memory and dream, beyond any connotation of time and space. Pasolini, on the opposite side, makes the places of his books and films so rough, carved, outlined a thousand times in their primitive essence to the point that, although in very different ways, he reaches the same goal, the estrangement, the dissolution of real variables that inevitably change the axes of history and topography.

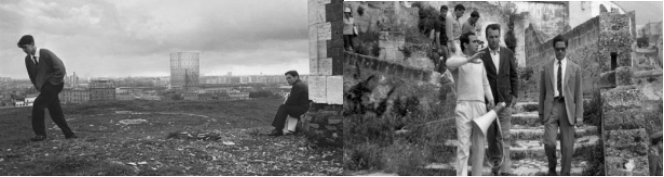

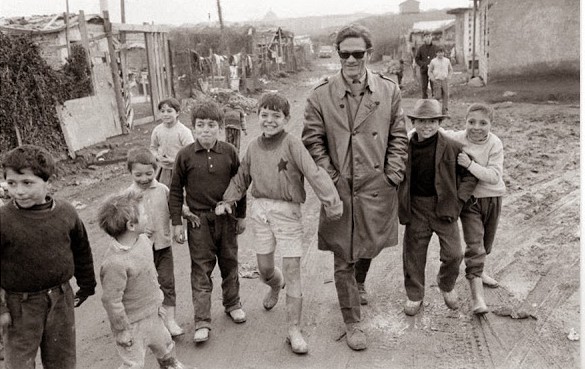

The topos become sites of the mind, coordinates of thought. They become places that elude any concrete connotation , any reality. They are incorporated and assimilated into the specific category of “pasolinian places”. Places where life burns like summer days . Between villages and “marane” life shows its harder face as the gaze of the poet wanders and investigates searching for that purity and genuine force of things, depriving the places of each monumentality and of each stylistic, as he explores with mind and heart the degradation of the suburbs, the empty spaces of the waste countryside, a paradigm of a bitter truth. Pasolini, for philosophical and ideological coherence, for revenge against the world, perhaps even for a pulse between heroism and self-injury, looked into the abyss, and, inevitably, he was attracted and absorbed.

The poet suffers the conflict between the residues of a Catholic and bourgeois culture treated against his will and the will to deny it, by restructuring its horizon , the art world and human lives. For this nude desire, Pasolini chose as the ideal icon a dark mirror, the ruin, the crumbling house, the spaces not reached by the concrete of the city. And this is the rough essence in which Pasolini moves his characters and his stories. Pasolini wrote : “I love life so fiercely, so desperately, that nothing good can come of it. And I believe that this ferocity, this desperation will bring me to the end. I love the sun, the grass and youth. The love for life has become for me vice worst than cocaine. I devoured my existence with an insatiable appetite.

And more:

I am outrageous; to the extent that I tend a rope – or better, an umbilical cord – between sacred and profane”.

Sacred and profane, past and present, reality and superstructures. These are the extremes that characterize Pasolini as a man and artist. If Fellini turned Rimini in the memory of a dream and Rome in a set for a film that constantly declares its fictitious nature, Pasolini chooses the opposite route: take off the veil of rhetoric, breaks the tourist brochures and the clichés created ad hoc by the subculture dominant, the Pro Loco and by local and state governments, which promote the progress and modern as the asphalt as a privileged way of being.

Pasolini travels with the typewriter and the camera throughout Italy and the world.

Pasolini travels with the typewriter and the camera throughout Italy and the world.

Bologna, cultured city but still subject to compromise and miseries typical of a small country.

The Friuli so “countryside” and Casarsa, the birthplace of his mother, Susanna Colussi , so raw and closed, hard of gossip that destroy everything that is “different”. Land of loneliness that leads to escape. Matera, a city of stone, so similar to the places of the crucifixion, at Golgotha that always represent the true misery, ruthless, dehumanizing.

Space for a truth that lives every day the dimension of the pain, almost a prehistoric essence that seems to be lost, but continues to exist, on the edge of everything, even the ability to conceive, to imagine it as existing .

The world then, the travels with Moravia, Maraini, Callas, to combine culture with the harshness of the truth. Yemen, Africa , the charm of art made of earth and mud, wonderful buildings in the raw nakedness of the desert. Art in the absolute silence and space for reflection. Upon returning from each trip, Rome, the “mother” city .

Mamma Roma, so different from his son, so far away and yet indispensable. The city that gives him the fame, the glory, the bread, but also with a clear but unspoken pact, death. The real one on the beach of Ostia, in a shroud made of grains of sand. A cruelly real scenery and at the same time entirely symbolic . Metaphor of blood. The Rome of Pasolini is the one of villages, beggars, people who live on the edge of a razor, sharp and deadly. People with an atavistic charm: an inexhaustible source of ink and images with a cruel, poetical hunger. So different and so similar to him. Pasolini eating it, satiates itself , knowing that these are foreign substances to the body, something far from his nature and cultured in an aristocratic background, in spite of everything, in spite of every choice and will. A systematic and deliberate poisoning, not to become immune, but if anything, hoping to die in an appropriate way, becoming what she said, the substance of his own words and his own shots.

To fill the gap between the real and the ideal, Pasolini, as mentioned, tends to bring the places of his existence to the original dimension, free from everything that has them transformed and standardized, or simply made modern. For Pasolini the artist must, through his work , store and protect a cultural landscape. In this perspective, the landscape is not only the geographical and natural environment, but also historic environment and human: a territory layered over time, which is both a linguistic universe, the identity of places, heritage and artistic images that transmits this environment . This explains why , in a fragment of a self portrait, Pasolini sees himself as a “force of the past” :

“I am a force out of the Past.

My love lies only in tradition.

I come from the ruins, the churches,

the altarpieces, the villages

abandoned in the Appennines or foothills

of the Alps where my brothers once lived.

I wander like a madman down the Tuscolana,

down the Appia like a dog without a master.

Or I see the twilights, the mornings

over Rome, the Ciociaria, the world,

as the first acts of Posthistory

to which I bear witness, for the privilege

of recording them from the outer edge

of some buried age. Monstrous is the man

born of a dead woman’s womb.

And I, a fetus now grown, roam about

more modern than any modern man,

in search of brothers no longer alive.”

Mamma Roma, so different from his son, so far away and yet indispensable. The city that gives him the fame, the glory, the bread, but also with a clear but unspoken pact, death. The real one on the beach of Ostia, in a shroud made of grains of sand. A cruelly real scenery and at the same time entirely symbolic . Metaphor of blood. The Rome of Pasolini is the one of villages, beggars, people who live on the edge of a razor, sharp and deadly. People with an atavistic charm: an inexhaustible source of ink and images with a cruel, poetical hunger. So different and so similar to him. Pasolini eating it, satiates itself , knowing that these are foreign substances to the body, something far from his nature and cultured in an aristocratic background, in spite of everything, in spite of every choice and will. A systematic and deliberate poisoning, not to become immune, but if anything, hoping to die in an appropriate way, becoming what she said, the substance of his own words and his own shots.

To fill the gap between the real and the ideal, Pasolini, as mentioned, tends to bring the places of his existence to the original dimension, free from everything that has them transformed and standardized, or simply made modern. For Pasolini the artist must, through his work , store and protect a cultural landscape. In this perspective, the landscape is not only the geographical and natural environment, but also historic environment and human: a territory layered over time, which is both a linguistic universe, the identity of places, heritage and artistic images that transmits this environment . This explains why , in a fragment of a self portrait, Pasolini sees himself as a “force of the past” :

“I am a force out of the Past.

My love lies only in tradition.

I come from the ruins, the churches,

the altarpieces, the villages

abandoned in the Appennines or foothills

of the Alps where my brothers once lived.

I wander like a madman down the Tuscolana,

down the Appia like a dog without a master.

Or I see the twilights, the mornings

over Rome, the Ciociaria, the world,

as the first acts of Posthistory

to which I bear witness, for the privilege

of recording them from the outer edge

of some buried age. Monstrous is the man

born of a dead woman’s womb.

And I, a fetus now grown, roam about

more modern than any modern man,

in search of brothers no longer alive.”

The first issue that comes to the attention of the young Pasolini, philologist and poet, is the link between landscape, memory and language. The language, in its plurality of traditions and faces, expresses a reality much richer and more than the one of the official territory of a country. Pasolini finds out with the Friulian dialect, which he used for his first collection of poems, Poems in Casarsa (1942), then expanded as The Best of Youth, (1954). Casarsa , the mother country, is a neo-Latin province: an atlas, therefore, not so much geographical as historical and linguistic.Casarsa

– like the meadows of dew –

trembling of yore

Learning to use the dialect as ” research tool ” implies a preliminary step: to learn the dialect. This is meaning if we consider that the Friulian was not normally spoken by the mother of Pasolini: the middle class, in fact, expressed in the dialect of Veneto. The dialect of Casarsa , however, is a native language, archaic, peasant, a sort of prehistoric mystery: hence the idea of a backward path ” along the degrees of being.” The dialect, for Pasolini, a well-educated writer with a sharp tongue and a rich, paradoxical eye, becomes a significant act of discovery but also of rebellion, almost an involuntary act of civil disobedience. The fact that Pasolini has also decided to represent a face poetically provocative. A first gesture of political consciousness.

In contrast to the rough areas of Friuli, the memory of Bologna, the years of training and reading, the years in which assimilates beauty and writing, magnificent portici and seminal books: ” The Portico of Death is the most beautiful memory of Bologna. It reminds me of the ‘ Idiot ‘ by Dostoevsky, it reminds me of ‘ Macbeth ‘ by Shakespeare, the first books I read. At fifteen I started to buy there my first book, and it was beautiful, because you do not read anymore, in all my life, the joy with which he was reading then”. It is ironic to note however in this autobiographical fragment, bitter irony in the names: even in years in which the poet breathes serenity, Death, from the Portico, it seems to send him a warning, an appointment for the near future.

Rome, then, is the third largest hub of the existence of Pasolini. The place that introduced him to the Renoir and Clair movies, which allowed him to approach the art of Giotto and Masaccio and start fundamental literary experiences as the magazine “Officina”.

The world of Pasolini became Rome. Even there, the first approach is linguistic. The input language is a creative interpretation of reality, a task crucial to frame and “photograph” a place and its socio- cultural landscape. And the Roman dialect sinks into life in the suburbs, just like the Friulian was on the life of the peasants. But Pasolini Rome is itself an icon of the language of things. It is the vitality of the boys yelled to life; is the grandeur of the past that coexists with the misery of the underclass neighborhoods; is the city of cinema, culture, squalor; of the temporal power, and a ” Jesus corrupt in the salons Vatican,” a papal city and a atheist one, in time and out of time.

With an almost cinematic technique, Pasolini made long tracking shots on Italy, that allow the creation of paintings of historical and geographical landscape . Here, however, returns to the initial question: are these paintings realistic or abstract, somewhat philosophical ? The second option prevails in view of what we said in this short excursus on the trail of one of the most complex and restless Italian artists of the twentieth century. Pasolini, in his books and in his films, always portrays his inner landscape, the idea of the world he wanted, loved and who was horrified, but he felt the only source of authenticity to draw from. At the risk of drowning in the well of uncomfortable truths and sharp as knives and screams and the crazy life of street boys.

Pasolini became himself at the exact moment he denies, he dinies what he really was. It goes contrary to him, flirting with the opposite side of its intrinsic nature, to express what he conceived as the only art worthy of the name: that rough, like the Giotto style of painting, far away from any inessential tinsel.

The paradox is that in his search for an Italy as it was, as was truly in a distant past and pristine, he ended up by reaching an accuracy documentary of an Italy of today, a part of the Country that we tend to hide, to ignore, removing it from the consciousness and posters.

Italy for Pasolini is raw, basic, so close to the size of the primitive, by contrast, as in a photograph overexposed, what really exists beyond the boundaries of respectable patina dear to tourists.

Pasolini had the task of telling something so pure and perfect, well characterized according to his way of seeing and thinking, as to appear disembodied, abstract and philosophical. But, in the end, his primitive world, dreamed, created, retrieved, cleansed of all tinsel, made it look just below the horizon of the buildings a reality more real than real, strong and desperate as his thirst and his hunger for life. That same life, which he looked straight in the eyes and led him to a death, which was, and is, symbolically, absolutely real, and yet already legendary, shrouded in mystery and silence screams, laughter and stupid and cruel grins. So much true to seem imaginary. Absolutely, “pasoliniana”.

Ivano Mugnaini

IVANO MUGNAINI si è laureato all’Università di Pisa. È autore di narrativa, poesia e saggistica.

Scrive per alcune riviste, tra cui “Nuova Prosa”, “Gradiva”, “Il Grandevetro”, “Samgha”, “L’ Immaginazione”. Cura il blog letterario DEDALUS: corsi, testi e contesti di volo letterario, www.ivanomugnainidedalus.wordpress.com.

Ha curato la rubrica “Panorami congeniali” sul sito della Bompiani RCS. Suoi testi sono stati letti e commentati più volte in trasmissioni radiofoniche di Rai – Radiouno. Collabora, come autore e consulente, con alcune case editrici. Cura e dirige i “Quaderni Dedalus”, annuari di narrativa contemporanea.

Ha pubblicato le raccolta di racconti LA CASA GIALLA e L’ALGEBRA DELLA VITA , i romanzi IL MIELE DEI SERVI e LIMBO MINORE.

L’algebra della vita (Greco & Greco, 2011), Inadeguato all’eterno (Felici editore, 2008), Il tempo salvato (Blu di Prussia, 2010)

Tra i critici ed autori che si sono occupati della sua attività letteraria ricordiamo: Vincenzo Consolo, Gina Lagorio, Ferdinando Camon, Raffaele Nigro, Giorgio Saviane, Paolo Maurensig ed altri.

Gionni Pucci liked this on Facebook.