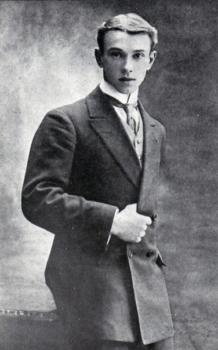

Vaslav Nijinsky is a myth of dance, extraordinarily beautiful and sensual, remembered for his genius’ turned into madness, a kind of schizophrenia driven by excesses of mysticism: a maniacal search for dialogue with God.

Vaslav Nijinsky is a myth of dance, extraordinarily beautiful and sensual, remembered for his genius’ turned into madness, a kind of schizophrenia driven by excesses of mysticism: a maniacal search for dialogue with God. Auden considered him a prophet, a suffering Christ. Everything was deduced from the pages of the Diary, confession of an artist torn by the impossibility of governing his genius.

Auden considered him a prophet, a suffering Christ. Everything was deduced from the pages of the Diary, confession of an artist torn by the impossibility of governing his genius. Considerations and judgments to be reviewed en bloc based on the real Diary, published at last without tampering or cuts. It is a text that gives us a paranoiac Nijinsky, crossed by bestial instincts, invaded by a pounding obsession of the body in its “low” forms (urine, excrement, raw sexuality) and by the chain of physiological processes (eating, digesting, eliminating ). Other than holy: here emerges a Vaslav light years away from the winged and literary image that the false Diario wanted to pass on to us. The book was written in six weeks, from 19 January to 4 March 1919.

Considerations and judgments to be reviewed en bloc based on the real Diary, published at last without tampering or cuts. It is a text that gives us a paranoiac Nijinsky, crossed by bestial instincts, invaded by a pounding obsession of the body in its “low” forms (urine, excrement, raw sexuality) and by the chain of physiological processes (eating, digesting, eliminating ). Other than holy: here emerges a Vaslav light years away from the winged and literary image that the false Diario wanted to pass on to us. The book was written in six weeks, from 19 January to 4 March 1919.

The great dancer, who has gone down in history for her extraordinary “performances”, was born on March 12, 1889 in Kiew. Childhood is poor and marked by hardship, but soon, following its inclinations and aspirations, it is welcomed in the St. Petersburg imperial ballet school.

Childhood is poor and marked by hardship, but soon, following its inclinations and aspirations, it is welcomed in the St. Petersburg imperial ballet school.

In 1907 he overcame the hard examination and was welcomed in the imperial ballet; once entered, he creates the role of the slaves of Armida in the “Armida Papillon” still by Fokine. Another important role shaped together with the inseparable friend and colleague is that of Cleopatra’s favorite slave in the “Egyptian Nights”. These are very important years because, in addition to success and personal confirmation, he has the opportunity to know another future “sacred monster” of the dance, that is Sergei Diaghilev to whom we owe the productions of the famous “Balletti Russi”.

These are very important years because, in addition to success and personal confirmation, he has the opportunity to know another future “sacred monster” of the dance, that is Sergei Diaghilev to whom we owe the productions of the famous “Balletti Russi”.

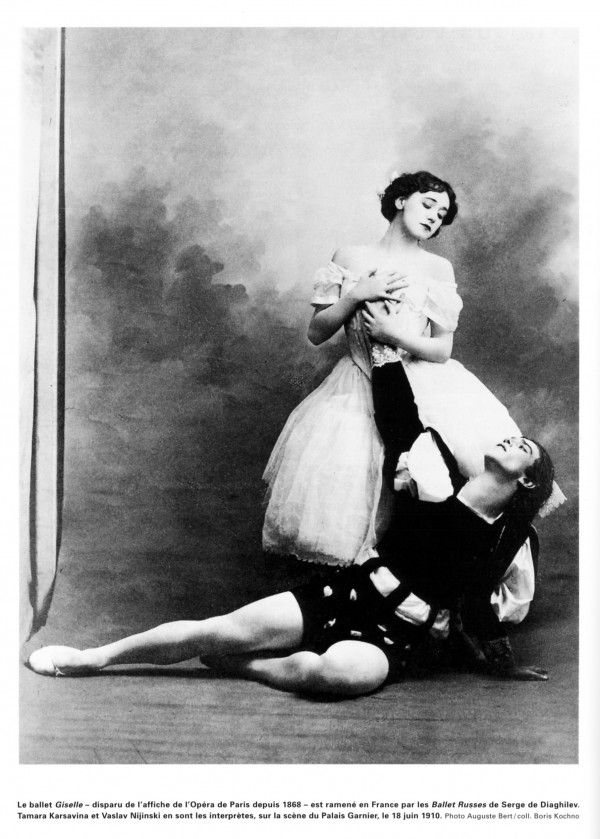

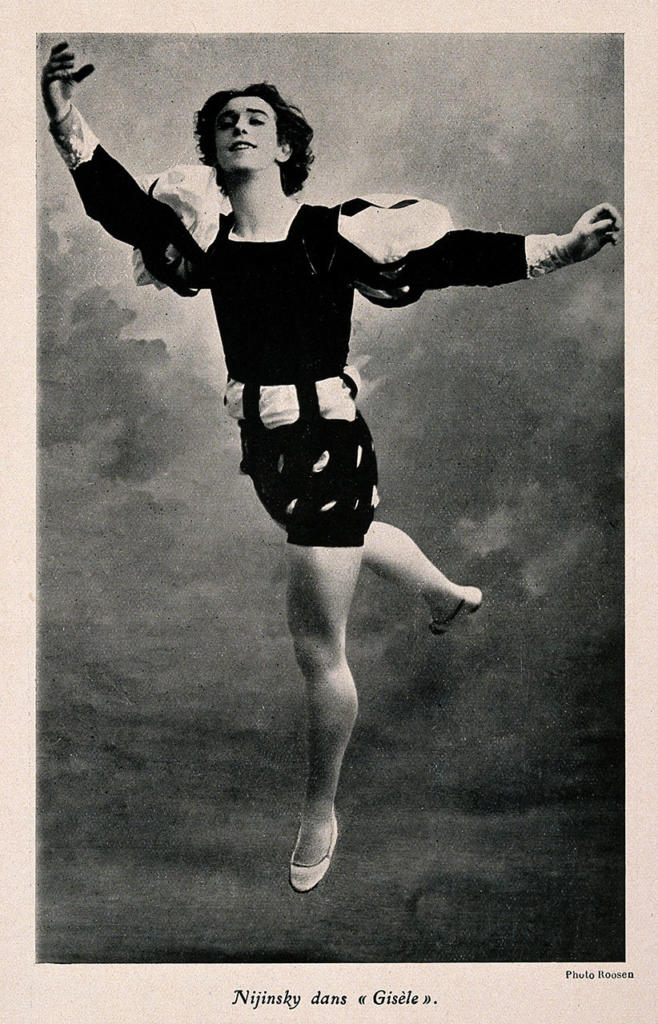

In 1909 he dances in an orchestral elaboration of the music of Chopin (as he was in fashion once), the “Chopiniana”, also by Fokine and he goes to Paris with the company put together by Diaghilev where he dances in the ballets “Le Papillon d ‘ Armide “and” Le Festin and Cleopatre “. In the 1909/10 season he dances in “Giselle” in St. Petersburg with Anna Pawlowa.

A year later, on a similar tour, still in the Parisian capital, he dances in “Sheherazade” (making the golden slave) and in “Les Orientales”.

In 1911, after having danced in St. Petersburg, Albrecht, in the so-called French costume, left for a third European tour of the Russian ballet with four new Fokine ballets: “Le spectre de la rose” and “Narcisse” in Monte Carlo (here he plays the part of the hero of the homonymous opera), “Le Carneval” (Arlecchino) and “Petrouchka” (in the main role) in Paris; in autumn the company is hosted in London with a two-act edition of “The Swan Lake” (where Prince Siegfried plays).

After long and exhausting tours around the world, he decided to devote himself to creativity, so here are born his brilliant choreography passed to history, his first ballet “The Apres midi d’un faune”, made on the homonymous orchestral piece of Claude Debussy. At the same time, and until the end of that year, he was in London, in several German cities and in Budapest, where he worked on the aforementioned “Le Sacre du printemps” by Stravinsky.

Next to the “Sacre”, Nijinsky choreographs another ballet, “Jeux” by Debussy again, both of them represented in Paris with great scandal, especially for the novelties introduced by the music of the Russian composer, judged barbaric and excessively wild. The public, in short, proves unable to appreciate one of the greatest musical masterpieces in the history of music.

After the great fuss and the “media” noise raised with the representation of the “Sacre”, he embarks on a South American tour, this time without Diaghilev. During the crossing, you trust the Hungarian dancer Romola de Pulzky. In a few months they get married in Buenos Aires.

After the great fuss and the “media” noise raised with the representation of the “Sacre”, he embarks on a South American tour, this time without Diaghilev. During the crossing, you trust the Hungarian dancer Romola de Pulzky. In a few months they get married in Buenos Aires.

Back home, following a series of irreconcilable misunderstandings, Diaghilev fires Nijinsky. The latter, then, takes to tread the scenes in a London theater with his own company but the experience ends with a financial fiasco.

The daughter Kyra is born in Vienna. At the outbreak of the First World War he was interned with his family in Budapest. The experience is traumatizing but not enough to bend the burning artistic temperament, in this singularly accumulated to the noblest scholarship of the Russian artists. He deals with a new company of Richard Strauss’s composition “Till Eulenspiegels lustige Streiche” (“Till Eulenspiegels”), another absolute masterpiece of a great musician; which bears witness to the intellectual and taste level that this extraordinary dance trio, as a whole, had developed.

In 1916 the Nijinsky went to Vienna and later to the United States; the fracture with Diaghilev meanwhile went in part by recompiling and back quindi dance with the Ballets Russes; in autumn a further tour of the company begins, where among other things there is the first sweat “Till Eulenspiegel”. Unfortunately, however, a new break with Diaghilev takes place: and Nijinsky, in search of peace and serenity, retires in Switzerland. Here his behavior begins to change considerably. The cause is soon explained: during a performance in a hotel in San Moritz (his last), in Zurich he is diagnosed with schizophrenic disorders. He died on 8 April 1950 in a London hospital. When Diaghilev launched him in 1909, Nijinsky was a very young pupil of the Petersburg dance school. In a very short time he would become one of the most revered and idolized beings in Europe – and the ‘cult’ has continued to this day. But the balance of the Nijinsky person was fragile: madness loomed over him, which would soon overwhelm him. And right on the threshold of madness Nijinsky wrote, in the winter of 1918-1919, this feverish Diary, to whom he wanted to entrust the truth about himself, in the terms he knew best, those of “feeling” (“I want to write this book to explain what is feeling “). With painful candor, with sharp jumps and surges, with maniacal hammering, between pauses of disarming sweetness, with the lucidity of delirium, Nijinsky traces here, fragment after fragment, his self-portrait – and together brings out his version of the history of the Russian Ballets . Diaghilev appears to you as a demonic being, in short memorable glimpses, not without their comedy; Stravinsky as a greedy and calculating spirit; and gradually the other protagonists of that whirlwind affair appear here pierced by an inexorable gaze – the look of the innocent who felt betrayed by the malice of the world, of the crowd that now oscillates between identification with Christ and an atrocious prostration, visited by the nightmares of blood and war. Great involuntary writer, Nijinsky makes us perceive in these pages a certain climate from which the Russian Ballets were born and lived. And it also shows us what species the immense power of his art was. Not only a stranger, but suspicious and hostile to the intellect, Nijinsky was dominated by an invincible vital pulsation, which he then desperately tries to transpose into a mystical vision (“I am a philosopher who does not reason – a philosopher who feels”; I have noticed that there are many human beings who do not palpitate “). Next to a large, conscious and perverse décadent, like Diaghilev, together with his impresario, his sorcerer and his lover, Nijinsky represented nature in its dark and fascinating intricacy: “I like hunchbacks and other monsters. I myself am a monster with feeling and sensitivity and I can dance like a hunchback. ” It was a portentous encounter, a tension that could not hold. After the break with Nijinsky, the Diaghilev ballets no longer find the splendor of the early years; as for Nijinsky, he becomes a mild recluse. Ten years after the writing of the Diary and the psychic crisis, Diaghilev wanted to bring Nijinsky back to the Opéra stage. But the great dancer did not recognize anyone, not even Karsavina, who had been his partner in Petrouchka. Shortly thereafter, Diaghilev would die in Venice. With them it was opened and the most extraordinary adventure of modern dance had closed.The manuscript of Nijinsky’s Diary was found by his wife, Romola de Pulszky, in a trunk in 1934. The same Romola took care of its publication in 1937, omitting, for reasons of opportunity, some passages, as well as the choreographic notations, of which he intended to prepare a separate edition. After the recent death of Romola, the complete manuscript of Nijinsky’s Diary was auctioned by Sotheby in London, with great fanfare, in July 1979.

Maximo De Marco began his career at an early age as a dancer, model, actor, singer, training and artistically perfecting internationally, winning a grant issued by the EEC (European Economic Community) that will lead him to study with teachers of World fame, later becoming author, director, choreographer, discographer, designer and writer, thanks to all these working experiences in the Entertainment World, today Maximo De Marco is one of the most important and internationally recognized Art Director , Nominated Art Director to Vitam by the Vatican, for the WYD and Friends of Pope Francis (World Youth Day), Official Member of the International Dance Council of UNESCO and Premio Cavallo D’Argento Rai (Italian Radio Television), Career of the Music Life Tv Awards (SKY) and of Cantagiro as best Artistic Director, Amen Prize for Literature with special mention at the International Exhibition the book of Turin in 2013 and winner of the Salerno International Film Festival in 2017 with his religious historical film “Petali di Rosa”. In his career as Art Director, he has directed Televisions, Radio, Magazine, Theaters, and great Star of Music and Performing Arts, including the English Pop Star Boy George, for his World Tour in the 90s “, the winner of The Voice of Italy Sister Cristina, and other artists such as: Franco Simone, Teo Mammuccari, Fabrizio Frizzi, Antonella Ponziani, Claudia Koll…